By Loren Hettinger — It’s that time of year again: the cooler mornings and a few golden leaves on the cottonwoods and willows remind us that cyclocross or CX racing is in full bloom. I can’t remember why I thought it would be a good idea to race CX. It couldn’t have been from spectating at a race in Colorado’s Chatfield State Park, south of Denver where I first witnessed people dismounting and running while carrying their bikes over barriers or up a steep bank. It all seemed counter-intuitive, or downright weird. Yet, there was an attraction–perhaps the challenge of doing something different after a road-racing season. This “something different” included riding on sketchy terrain with off-camber turns, slippery grass, and even ice-infused mud, while trying to stay upright.

For any of us who transitioned to CX from road racing later in life, the process was generally not seamless, as CX was a new and different “animal.” As different as a person proficient at loping around an arena on a horse, maybe doing some pole bending, but then decided to become a trick rider, suddenly attempting forward fenders, one-footed stands, and galloping vaults. Watching the top guys racing CX was vexing: the seamless dismounts, hurdling barriers while carrying the bike, and then remounting as if the barriers hadn’t been there in the first place. A few of us practiced this craft, starting slowly by dismounting to one pedal and then throwing the off leg back over, then gradually dismounting, running with the bike, and trying to remount without inflicting excruciating pain on ourselves. Landing too hard on the saddle, the top tube, or onto the rear tire was not for those with a low tolerance for pain! We practiced our new craft endlessly, even had some coaching, and watched videos of the Euro pros, as if their awesomeness could somehow transfer to our brains and increase our coordination.

Dismounts and remounts weren’t the only difficulty because CX racecourses were an education in off-road surfaces. I had ridden mountain bikes on Front Range trails, but not raced them yet, and until now had thought the riskiness of a criterium was the epitome of prerace jitters. Moreover, CX course planners looked for the sketchiness, as if a slightly wider, knobby tire could be successfully ridden on any surface. And the treacherous surfaces naturally increased with the onset of winter. Another interesting aspect about this sport was the persona of CX in general—that real CXers thought the sketchier the course and conditions the better. I tried to see this point of view, but secretly thought these people were lying or at least pretended to buy into this macho psychosis while secretly hoping for a dry course on gentle trails like I did. It took a while until I too could revel and smile in the mud.

Then there was the application of infantile skills to courses during a local race. I had never been gassed in a road race to where I actually stopped or plodded up a steep hill in a death-march, bike over a shoulder, breathing like the bellows of hell’s fires, (or as one teammate described, “Like a steam locomotive!”); but CX racing had this effect. Another compounding factor was my first, too large, converted touring bike, which seemed to get taller during a race. Initially, I kept my objectives simple: not crash or fall over and hurt myself, not be rooted somewhere on the course, and not finish last.

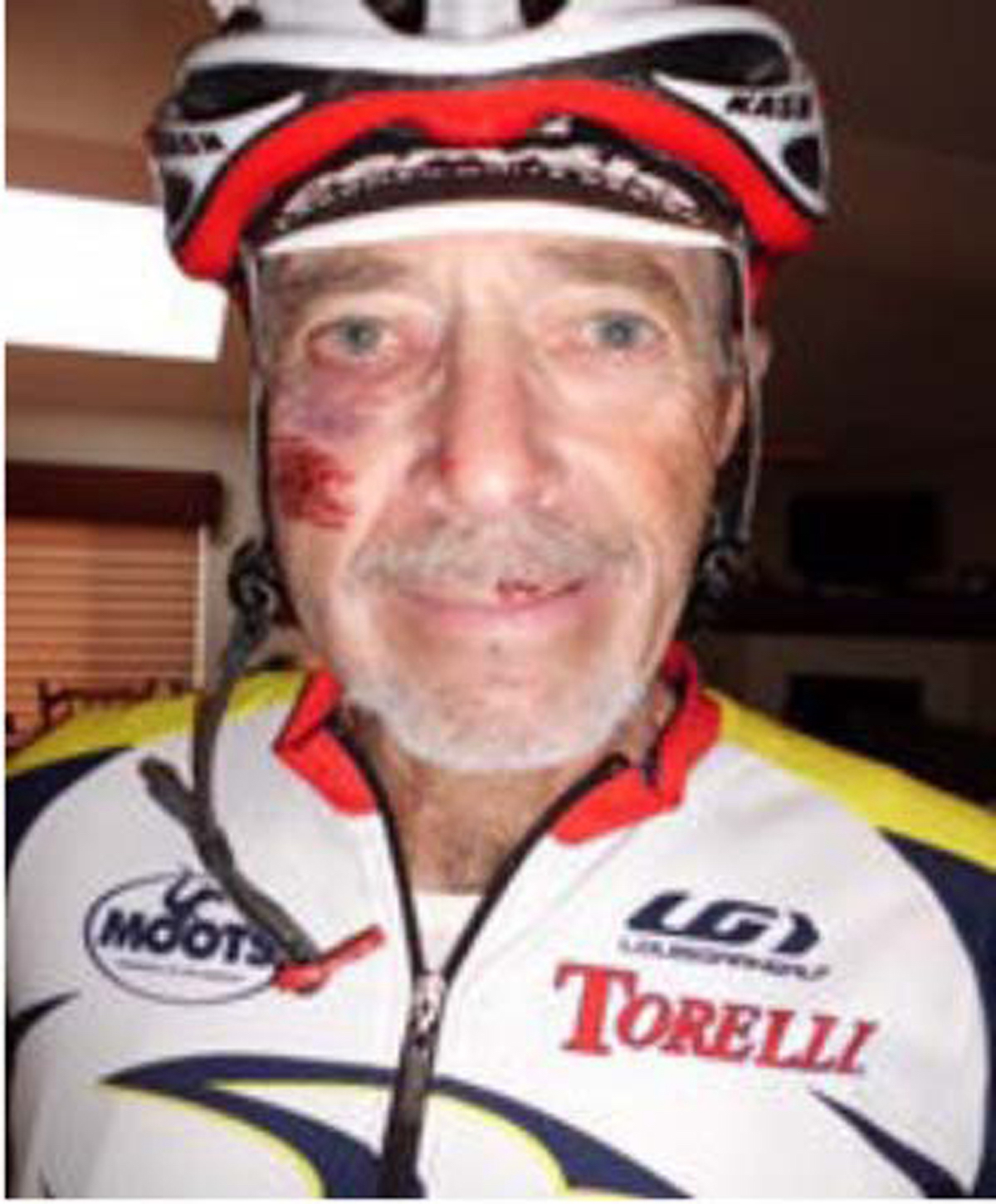

Of course, there were more than a few times when at least one of these objectives was not met. Some have remained somewhat vivid; like a race at the Boulder Reservoir when I cut a shin into the sub-cuticle by falling onto my bike in a tangle with other riders. Another episode occurred on a course through the marshes interior to the Mead sportscar racetrack. The driver error consisted of sticking a front wheel into a hole of muddy water–that I knew should have been avoided–resulting in a face plant and flattened nose. Seeing the bottom of shoes and cleats from ground level as other racers jump over you is disconcerting. Worse than that is searching that puddle, raccoon-like, for a lost lens from my glasses only to find that it was plastered to my beard in adobe-like goo. Riding with cotton gauze hanging from one nostril and one lens to sight the course was somewhat detrimental to not being last. Okay, so many of my objectives could be obliterated at a single race. How about all of them in a single helping?

This larger serving occurred at the Xilinx State Championships one wintry day. I rode several warmup laps and noticed with some interest a large flagstone bridge crossing of a ditch. My concern was the six-inch flagstone edge; however, I “lifted” the front wheel onto it during the first approach and confidently rode on.

The Masters’ group lined up in about three rows of seven across. Starts are generally hectic. All of us want to get toward the front before the courses narrow and enter off-road sections, single-track, or grass chicanes. I sprinted with the rest around a coned parking lot and then into the sand of a volleyball court. I remounted after the sand run, breathing hard. A familiar competitor was in front of me, and in moving to pass him, the flagstone bridge suddenly appeared. I belatedly thought about remedial action, but instead “endowed,” landing mostly on my left elbow—all this occurring in . . . what, under a second? Lying on the side of the stone was at first embarrassing, then disturbing, and finally all that psychological turmoil was replaced with acute physical pain. Other racers went by giving me the look of, “What happened?” or “Better you than me!”

Continuing crossed my mind, but I knew my race was over while attempting to straighten the handlebars and a brake lever. The injured arm responded by circumscribing some airy signals, as if trying to communicate with someone farther down the course that it knew, and I didn’t.

As I retrieved my spare wheels and packed things into the car, the thought that the injured appendage might not be an easy fix was reinforced by the throbbing and continued uselessness of the arm. By the time I headed back toward Longmont and the retreat toward home–pausing to search for ice at a convenience store–the elbow was the size of a softball.

X-rays later revealed that I had fractured the olecranon process (yeah, the elbow-pointy thing). This culminated in a kind of injury from hell: surgery to install hardware, a second, larger surgery 10 days later to check a nasty staph infection and replace the hardware. Then a Groshong catheter was plunged into my chest for six weeks of antibiotic infusions (when I really seriously considered experimenting with vodka), and finally physical therapy to unfreeze the joint.

I sometimes wondered in growing up and reading adventure stories of the American West if I would have been able to hack the Sundance Ceremony of the Plains Indians. This ceremony consisted of a bone being inserted through the chest muscles of the aspiring warrior who gradually pulled free of it and the leather thongs that were attached to a pole. Or, if I would have had to carry wood and water for the women of the tribe all my life. By the time the catheter was tugged out of my chest, I was more confident of my warrior aspirations and stopped for a double espresso on the way home.

There was another undercurrent to this experience: that the glitches and driver error-injuries were just reminders of something that we already knew: that bike racing can be dangerous. However, the rewards must outweigh the risks. Or, maybe it’s as Mark Cavendish said, “You know that thing in your head that says, ‘You shouldn’t be doing this?’ Well, we don’t have that!” But about the rewards . . . a sense of achievement, the challenge of a course and whether you could ride it or mostly ride it and with progressively more skill each lap. One could always hope. There is no doubt that for me it was addictive, and it must have been fun too. Because if it wasn’t, why do it? As one of us in the peloton said, “About as much fun as that first kiss by a fourth-grade crush!”

Some of my family and non-cycling friends thought that this medical sojourn would be the final nail as a deterrent from the rigors and risks of CX (and perhaps to bicycle racing in general). But the mishaps instead spurred me into increasing the reward side of this risk equation, and somehow becoming better at the craft. In fairness to CX and in defense of my seemingly ineptness, there were a lot of seasons when I had no mishaps needing medical attention. I may have ridden a few near-perfect laps, and the sketchy sections of a course were traversed in an upright, exhilarating manner. Perhaps, it’s not just the pros like Mark Cavendish, but a lot of us CX cyclists don’t have that “thing in our heads.”

(Visited 89 times, 1 visits today)