At Paris-Roubaix, more than any other single race in professional cycling, technical innovation is given free rein in the pursuit of a decisive advantage. The rider and the mechanic’s foe is the same – the brutal cobbles of northern France – and the bikes that are ridden there are sometimes innovative, sometimes bizarre, and perpetually fascinating.

Roubaix, 2003.

The leading trio ride under the flamme rouge, soft-pedal a little, and start to prepare for the one-and-three-quarter laps of a velodrome that will decide a day of brutal racing. The winner of this monument will come down to one of three riders: Peter van Petegem, a Belgian in the rainbow kit of World Cup leader; Dario Pieri, a crimson mountain riding for Saeco; and Viatcheslav Ekimov, an Olympic gold-winning powerhouse of US Postal Service’s lineup.

Entering the Roubaix velodrome, van Petegem forces Pieri to the front. For a lap, the race is suspended in an uneasy stasis. The Russian, Ekimov, is first to blink. He drops down the bank, from the back to the front, but van Petegem has the answer to the acceleration and sweeps past on his way to an ecstatic victory. An exhausted Ekimov sits up, hands on hips, and Pieri rides to a career-best second, hanging his head in mute resignation as he crosses the line.

The final three, Roubaix 2003.

The race footage is grainy now, with that kind of warped and washed-out look that old recordings have, but if you squint at Pieri’s red Cannondale through the race, you can just make out a rubbery yellow suspended section below his headtube.

That bike – an aluminium Silk Road model, with a ‘Headshok’ suspension system – would, for the next decade, be the last suspension-equipped bike to be ridden to a podium at Paris-Roubaix. But it wasn’t the first.

A location for innovation

Paris-Roubaix’s constituent parts are of such unusual toughness that it’s not so much a race as it is a kink for riders and a fetish for fans. The farm roads of northern France, through the verdant fields and decaying industry of the Nord, are distinguished by cobbled sectors of bike-breaking brutality, with names that become legend: Carrefour de l’Arbre, Mons-en-Pévèle, Trouée d’Arenberg.

If you’re an exceptionally strong rider of a certain skill set, and you navigate these sectors and all the others with luck – always luck – on your side, you might win the Hell of the North.

Even then, as Pieri found, you probably won’t – but a good mechanic, a supportive sponsor and a bonkers bike can certainly help stack the deck in your favour.

The history of weird bikes at Paris-Roubaix is long and varied, but had its most glimmeringly golden era in the early- to mid-1990s, when suspension became, for a brief stint, the winning advantage. Surprisingly, however, the rider ushering in this era was not some forward-thinking prodigy, but a grizzled French veteran called Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle.

Gilbert Duclos-Lasalle, 1992.

Duclos-Lassalle, riding for the Z-Lemond team, had turned pro in 1977, and in 1992 was riding his 14th Paris-Roubaix. He’d made a name for himself as a man for the classics, with two second place finishes at Roubaix in 1980 and 1983 showcasing his artistry in the cobbles’ brutality. In 1984, however, his career almost came to a premature end when his hand was shot and shattered in a hunting accident. He lost most of a season in recovery.

By the late ‘80s, in his career’s second act, Duclos-Lassalle had settled into a role as road captain. In 1990 he was a loyal lieutenant for Greg Lemond in the Tour de France, helping deliver the American star to his third and final yellow jersey – curiously enough, after Lemond’s own near-career ending hunting accident.

In 1992, Duclos-Lassalle was 37 years old and in the twilight of his career, but his team had a trick up its sleeves on the startline of Paris-Roubaix: an extremely custom fork from the ascendant mountain bike suspension brand, Rock-Shox, that they’d begun experimenting with a year earlier.

Six and a half hours later, a dust- and mud-splattered Duclos-Lassalle soloed into the Roubaix velodrome a lap ahead of the next closest rider, raised both arms over his head and changed the trajectory of bike tech at the cobbled classics forever.

Duclos-Lassalle in the closing stages of his debut Paris-Roubaix win, prior to striking off alone.

Duclos-Lassalle’s win was a result of good luck, positioning and grit, but having a suspended front-end obviously helped reduce the battering from the cobbles. The fork was crude by today’s standards, but as Sander Rigney, SRAM’s VP of Product Development recalls, the “highly modified” MAG 21 SL Ti mountain bike fork “was our top of the line offering at the time.”

“It featured an open bath, air/oil system with compression adjustment and a lockout with a blow-off. This was a revolutionary feature at the time, allowing riders to run the fork very stiff, yet still retain some compliance and movement when needed. Travel was reduced for the road version, and a custom arch was created to accommodate the larger diameter tires,” Rigney told CyclingTips.

Of course, being the 1990s, ‘larger diameter’ is a relative term – the absolute-upper limit for its clearance was 25mm, not that anyone was running that size then. It wasn’t without its foibles, either. A contemporary tech write-up describes it with a touch of affection as “exceedingly flexible” and “a gigantic boat anchor”. But with Duclos-Lassalle’s result catapulting the fork into global prominence, it was widely adopted by teams at the race the next year and Rock Shox was soon fielding requests for a commercially-available variant.

Duclos-Lassalle was able to defend his title the following year, beating Franco Ballerini in a memorable photo finish that saw Ballerini celebrating extravagantly before the Frenchman was confirmed the winner, sending the local crowd into a chanting rapture.

On his bike, again, was that fork – as was the case for half of the peloton the following year, when Andrei Tchmil slid through a muddy quagmire to break Duclos-Lassalle’s late-career streak, making it three in a row for Rock Shox.

At 38 years old, Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle won a second consecutive Paris-Roubaix in 1993, beating Franco Ballerini with a throw to the line. Ballerini wasn’t using a Rock Shox fork, but had another curiosity of the era on his bike: an Alsop suspension stem.

Andrei Tchmil battles treacherous conditions on his way to the win in 1994.

From forks to frames

Spurred by the success of suspension, other brands rushed to produce game-changing breakthroughs in their own battle against the bumps.

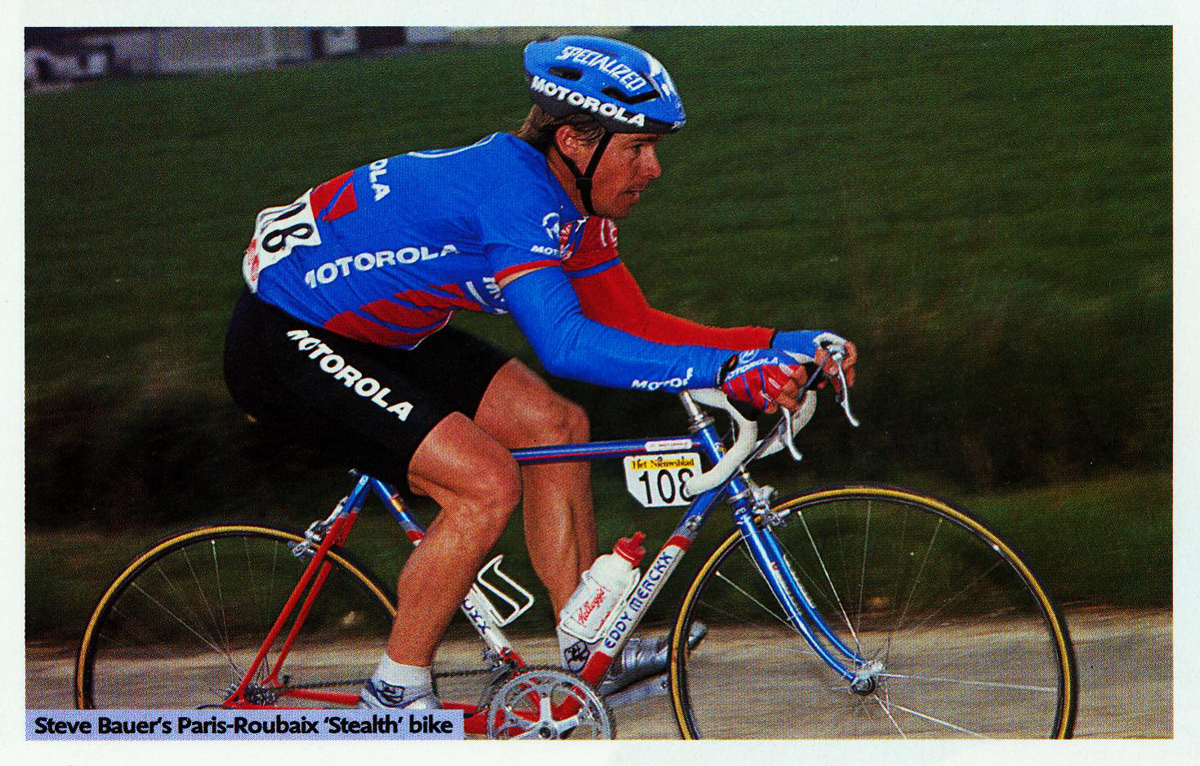

Motorola’s Steve Bauer, second in 1990, had one of the most bizarre designs to grace the cobbles in 1993, with a long wheelbase and slack (60°!) seat-tube that was unlike any bike to be raced at Roubaix either before or since.

Photo: Flickr Commons, photographer unknown.

The ‘Stealth’ bike was, according to Bauer, an innovation that was based more on third-hand intuition than any actual tested benefit: “Richard Dejonckheere, brother of the Motorola sport director Noel, had been riding one day and spotted a cyclo-tourist riding this weird bike with a long wheelbase and laid-back seat angle,” Bauer told Rouleur. “Richard said the guy was generating lots of power on the cobbles. So we went to Eddy Merckx, who was building our bikes at the time, gave him the specifications and asked him to build it … Eddy was not impressed, but he made it.”

It didn’t pay off for Bauer – he finished 23rd, and lamented later that the bike was “good and stable, and you could generate power, but it was just not agile enough.”

Bianchi – not a brand I’d nowadays associate with innovation, I’m sorry to say – was even more forward-looking in its designs, despite retaining most of the established norms around geometry.

Bianchi-sponsored teams in 1994 had access to dual-suspension designs such as these.

After Ballerini’s humiliating second place on a Bianchi in 1993, the brand went all-in for 1994 and built a number of dual-suspension bikes for Gewiss-Ballan.

They also came to the party with a wild one-off duallie for GB-MG Maglifico’s star rider, Johann Museeuw. That bike, designed by Bianchi USA’s product manager Matt Harvey, featured a single-pivot swingarm, a coil rear shock, and a seat-tube mounted rocker link, along with a Rock Shox fork and a non-diamond frame.

Johan Museeuw on his unique dual-suspension bike, 1994.

Museeuw wasn’t the only high-profile rider to line up in Compiegne on a dual-suspension bike: Gan teammates Greg Lemond and Duclos-Lassalle starting the race with titanium-framed bikes with a rear shock activated by a Gripshift lever mounted to the handlebars, in addition to the now de rigeur Rock Shox fork on the front.

A muddied, bloodied Lemond in the 1994 edition of the race. Note the Gripshift lever next to his left hand, which controlled the rear suspension.

Lemond and Duclos-Lassalle were forced to swap their bikes out early in the race, but Museeuw was having a monster of a ride, and his Bianchi was performing superbly … until 24km to go.

With Tchmil solo off the front and Museeuw in hot pursuit, the chain-stay snapped straight through. That, paired with a clumsy bike change, condemned a devastated Museeuw to a suitably unlucky 13th-place finish. The bike’s designer later lamented that the failure had been the result of a disagreement between himself and the factory about the choice of materials: “a cromoly rear end can flex thousands of cycles … whereas the Italian factory, against my pleading, made it out of 6061 [aluminium] without heat treating it.”

Bianchi’s final dual-suspension play at the race was in 1995, with the Gewiss-Playbus team riding a titanium model with an updated design to an unspectacular 20th place under Stefano Zanini.

Stefano Zanini on Bianchi’s final dual-suspension road design at Paris-Roubaix.

The tide was beginning to turn, however. That year, the supercharged Mapei team roared to prominence, scooped the win five times in the next six years, and even going as far as claiming all three podium positions on three of those occasions. Their bike sponsor, Colnago, was staunchly anti-suspension.

Winning products shift units, but they also set trends, and the very public failure of Museeuw’s bike in 1994 and Mapei’s dominance put a major dampener – no pun intended – on road suspension innovation.

Gianluca Bortolami, Johan Museeuw and Andrea Tafi scoop the podium in the 1996 Paris-Roubaix.

Rock Shox, having ruled the roost for three heady years and occupied a virtual monopoly in the space, rushed to maintain its position, moving to mass production. “Eventually, we offered a product for sale, dubbed the Paris Roubaix SL. For a variety of reasons – weight, price, geometry, to name a few! – it was never commercially successful,” SRAM’s Sander Rigney told CyclingTips, with disarming frankness. “A few years later, we launched a far more refined fork for road, called the Ruby SL. While much lighter and aesthetically closer to a traditional road fork, it also had very limited commercial success.”

A new era

Road suspension needed a standard-bearer, and it found it in Cannondale. From 1997 to 2004 Cannondale sponsored the Saeco team of Italy, providing its riders with a series of now-iconic aluminium framesets, and, in the cobbled classics, Headshok-equipped bikes named the Silk Road.

The Headshok design originated from the brand’s mountain bike lineup, and the road-modified version gave riders 10mm of travel, greater torsional stiffness than the dual-leg Rock Shox fork could muster, and in later years, even an electronic lock-out.

Mario Scirea on a first-era Silk Road, 1997.

As the inventor of BB30 and Hollowgram cranks, Chris Dodman – Cannondale’s Advanced Projects Engineer – has overseen a number of the brand’s important innovations, and started at the company in the same year that the Silk Road was launched. “We saw Headshok as a technology that could benefit all platforms whether road or mountain and at the time there was an opportunity for Cannondale to be disruptive in the road space,” Dodman told CyclingTips.

“On the Paris-Roubaix podium bike [Pieri’s, in 2003], we stuck with 10mm of travel with a 23mm tire which equated to the feel of a 33mm tire. With the full lockout on the Headshok riders could switch between the feel and efficiency of the 23mm tire or improved ride quality and traction with the damper open that you would get with a 33mm tire.” That lockout was operated, Dodman says, by a “proprietary electronic lockout with a rocker switch hidden under the hood of a Campy lever.”

The lockout may have been clandestine, but the Headshok on Pieri’s bike itself was a big, yellow and squishy showcase of Cannondale’s innovation. The Silk Road’s shock was coil sprung with a concentric elastomer “for a progressive yet bottomless feel” that was a good deal more sophisticated than Rock Shox’s offering of a decade earlier.

Three tech solutions of Paris-Roubaix 1998: Michael Rich, on a more refined Silk Road, leads Tom Steels (Mapei) on a traditional Colnago road bike, with a Rock Shox fork on the third rider in frame.

The Silk Road was the most obvious example of technical trickery at Roubaix in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but it wasn’t a lone innovator, with another American brand in the fray. Trek’s discreet softtail suspension design on US Postal’s OCLV frames took some of the sting out of the cobbles, providing 13mm of rear compliance and helping Ekimov to that third place behind Pieri in 2003.

It was one of those bikes, in fact, that was catapulted to brief global notoriety when George Hincapie’s steerer tube failed in the climactic moments of the 2006 race. That was no fault of the bike’s back end, of course, but it was a poignant demonstration of Paris-Roubaix’s capricious temper.

A devastated George Hincapie rues what could have been, 2006.

Meanwhile, most other brands were beginning to discover what seems so obvious now: that a bigger tyre and lower pressures could provide similar benefits to what the engineers of the 1990s were trying to achieve all along.

Longer seatstays, as on the Cervelo R3s ridden to victory by Stuart O’Grady and Johan van Summeren, helped add comfort, stability and tyre clearance. And where a brand’s existing road frames lacked clearance, cyclocross bikes with cantilever brakes were pulled into service, along with cruder time-honoured tricks like a double wrap of the handlebars.

The last Paris-Roubaix to be won on a metal bike was Magnus Backstedt’s 2004 victory, astride a titanium Bianchi. Every Paris-Roubaix since has been won on carbon fibre, with engineers refining their offerings year by year – lighter, more compliant, better handling, stronger.

Very tall Swedish man Magnus Backstedt wins Paris-Roubaix in 2004, on a titanium frame.

Looking forward, looking back

By early last decade, Specialized’s Roubaix and Trek’s Domane had emerged as the quintessential Paris-Roubaix bikes under riders like Tom Boonen and Fabian Cancellara, and in the years since their record both at the race and on the sales-floor has been impeccable. In the last 12 years, the Specialized Roubaix has been ridden to victory at its namesake race on six occasions under riders from Boonen to Sagan to Gilbert.

Today’s bikes of the classics have distilled the lessons of the previous thirty years into their DNA, not that their manufacturers are inclined to downplay their own achievements. But by looking at the bonkers bikes of Paris-Roubaix in the 1990s and the early 2000s, you can trace a clear lineage from then to now.

Picking your way through the last couple of decades of tech, you can begin to see how Trek’s discreet IsoSpeed decouplers could have evolved from a softail design, how Pinarello’s electronically-controlled dual-suspension set-up is a distant relative of Museeuw’s Bianchi, and how Specialized’s ‘FutureShock’ front suspension, giving 20mm of vertical compliance above the headtube, has a debt to Cannondale, and likewise from Cannondale back to Rock Shox.

In 2018, world champion Peter Sagan attacked from the peloton and bridged across to the remnants of the break (including Silvan Dillier, rear). Sagan and Dillier went to the finish together where Sagan comfortably won the sprint. It was the first win at the race for Specialized’s FutureShock-equipped Roubaix.

Roubaix, 1992.

In 1992, in the Paris-Roubaix that changes everything, Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle ploughs headlong over the cobbles in a massive gear. Alone off the front, he holds his lead into the gritty outskirts of Roubaix, and there, he flies round the right-hander into the velodrome. Dust-coated and with his hair slicked back by the frigid breeze, Duclos-Lassalle’s mouth hangs open. His body is locked over the bars, rocking back and forth in the drops. Watching the footage today, as he takes that corner, you can almost feel the torsional flex of the forks at the front of the bike. An instant later, he’s onto that sacred, smooth surface; untouchable, immortal.

The underdog stalwart of French cycling pumps his fist once, twice, and then sits up to salute the crowd, who are in various states of losing their shit. At the front of his bike, if you squint through the time-warped footage in your Youtube window, you can see the champagne-coloured Rock Shox forks that were his secret weapon.

And here’s the thing: I swear, in the fatigue and the joy and the triumph of that moment, you can see the ripples of Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle in all the editions of Paris-Roubaix since. It’s in Gilbert, in Sagan, in Cancellara, and it’s in the bikes that carried them there.

Andrei Tchmil’s 1995 bike at Paris-Roubaix, featuring the famous Rock Shox fork. It would never again be ridden to a win at Paris-Roubaix.